Wednesday, March 29, 2006

Land rights and the World Bank

In justifying his order, Tuilaepa said the statement was grossly defamatory. "In my opinion as leader of the country, they have gone overboard the decency level of political campaigning," he said. "My decision is to protect the electoral system in the future...You can't just make misleading statements about these things and expect to get away with it. What these people have done is that they have overstepped the mark." So it would seem that Tuilaepa is acting on behalf of the Government of Samoa. But on what grounds could the Government take these individuals to court?

On the basis of Tuilaepa's comments, the court action will probably be based on a claim of defamation. Yet, SDUP deputy leader Asiata Saleimoa Va'ai (himself a lawyer) says, "There is no such thing as defaming a government...Only a person may be defamed." If this is true (I have absolutely no idea) then Tuilaepa can really only claim personal defamation. The consequence of which would mean that it would be wrong for him to use Government resources to make his case in court. Until the details of the case are known, which I'm sure will only emerge after the election, little more can be said.

All of this talk however, dances around the real issue. Is there an existing agreement with the World Bank through its International Development Agency and what are the details of such an agreement? Does the HRPP intend to change land registration legislation to make the registration of customary land conform with the Torrens system used for freehold land? Tuilaepa has, as yet, failed to answer these questions properly. The SDUP and the Samoa Party have also failed to really provide the kind of proof that would make their allegations iron-clad. Whatever the outcome of the election on Friday, this story is far from finished.

Tuesday, March 28, 2006

Samoan Politics

For the last 23 years

The major planks in the HRPP election platform are economic growth and infrastructure development. Tuilaepa, and the Deputy PM and Finance Minister Misa Telefoni, regularly point to the sustained economic growth

Is this enough to get the HRPP over the line? Many suspect it is, but there is a growing sense of tiredness at the continued rule of the HRPP. Le Mamea R Mualia, head of the main opposition party the Samoa Democratic United Party (SDUP), has been polling very well over the last couple of months. He has consistently polled ahead of Tuilaepa as preferred leader and the SDUP has enjoyed several poll "wins" ahead of the HRPP.

The SDUP has focused on three main areas for its campaign: health, education and governance. If elected, the SDUP would conduct a review of teachers' pay and make a strong push to provide free and compulsory primary education. This has been received quite well but it is perhaps the issue of health that resonates strongest with the Samoan people, thanks to the bitter pill of an eleven week strike by

Two major problems plague the public health system of

A more immediate challenge for the present Minister for Health is election rival Su'a Rimoni Ah Chong. Su'a, head of the Samoa Party (SP), is perhaps the most outspoken of all the party leaders. Whilst the SP and the SDUP share their concern about governance, it is Su'a who has really championed this issue ahead of all others.

Su'a is well qualified to campaign on this issue, as he was formerly the Samoa Controller and Chief Auditor. In this role, Su'a issued a report in the mid nineties that implicated a number of cabinet ministers and senior government officials for fraud and other misdemeanors. The report led to his dismissal and amendment of the Samoan Constitution.

Su'a wants to see independence brought back to many government portfolios, most notably the oversight agencies of the Audit, Electoral Commissioner and the Attorney General offices. A significant reduction in government wastage features strongly in the SP manifesto as well.

Are these issues really the ones foremost in the minds of most Samoan voters? The issues of health and education most certainly hold the interest of the voting public but other issues such as land ownership are also extremely important. There are currently two large land title claims before court and allegations made by the SDUP and SP last week have put the HRPP under scrutiny. The allegations hold that the HRPP reached an agreement with the World Bank to reform the ownership of customary land (which represents 80% of all land in

In spite of these concerns, it would seem that the HRPP are going to win the election. Most of the people I have spoken with about the election seem pretty convinced of that. By themselves, neither the SDUP nor the SP would ever have the numbers to form a majority government, and with the HRPP fielding twice as many candidates as the SDUP (which has fielded more than the SP), the numbers do seem to stack up in the HRPP’s favour.

Still, the SDUP in particular have done well to present themselves as a credible alternative government. They have argued their platform consistently, clearly and early. It’s a lesson the Australian opposition parties could do well to learn from.

Thursday, March 23, 2006

Crab for dinner

A few weeks back I chanced upon a man selling freshly caught crabs on the side of the road. Seeing crabs this size is a bit of a rare thing, so I did what any sensible person would do and bought two of them immediately.

I invited a few friends over and we had a great meal. Rice, steamed chinese greens and chilli crab. And the requisite cold Vailima of course. Very nice indeed!

Sadly I haven't seen anyone selling crabs since. There aren't too much shellfish and crustaceans available in Samoa and I'm not too keen on getting up at 5am to head to the fish market to really see what's available on a regular basis. So for now I shall just have to hope that luck is with me whenever I walk down the road.

The power of village politics

Samoans head to the ballot boxes at the end of the month. The election itself warrants at the very least a post of its own, so for now I'll supply only the barest of detail (sorry). Parliament has 42 seats, 40 of which represent village constituencies. Each constituency is typically comprised of several (say two or three) villages and most constituencies have a single sitting parliamentary member.

One such constituency is that of Faleata East. It is comprised of the villages of Lepea and Vaimoso. Prior to the 2001 elections, the villages came to an agreement stating that they would take turns fielding candidates to represent their constituency. Under this agreement, Faumuina Anapapa of Lepea, was elected unopposed. Anapapa was appointed to a new post in 2002, leaving his parliamentary spot vacant. Once again honouring the agreement, Vaimoso village did not field a candidate and Lepea's Lepou Petelo II replaced Anapapa.

By virtue of the standing agreement between the villages, Vaimoso expected to field its own candidate without opposition from Lepea. Both Vaimoso and Lepea residents were shocked to learn that Lepou has registered as a candidate for the upcoming elections.

According to news reports over the weekend and in Monday's Observer newspaper, the Lepea village council (their fono ale nu'u) acted swiftly to punish Lepou for his actions. Lepou and his family were told, in no uncertain terms, that they were to be banished from the village. They were to have until 4pm Monday to comply by the order.

Tuesday's Observer provided the next chapter of the story. The Land & Titles Court, responsible for mediating issues of customary land and matai title ownership amongst other things, ruled that there was nothing in Samoan legislation that specifically denied Lepou the right to stand as a candidate. This in itself was not particularly surprising I suppose. However, Lepea's response was to _decide_ to allow the Land & Titles Court ruling to stand strikes me as a fine indicator of the power (if not always absolute) at the village level.

Some colleagues at work have told me that in similar situations in the past, where a family has been banished only for the decision to be overruled, it has not been uncommon for that family's house to be burnt down and for the family to be otherwise ostracised from the community anyway. I doubt strongly that something like this might happen in the case of Lepou; the real test will be which way the members of Lepea vote come election day.

Tuesday, March 21, 2006

"If it's bad...it must be good!"

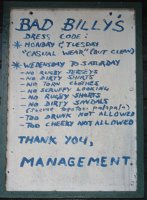

So reads the slogan for Bad Billy's, one of the premier bars/clubs in Apia. It's not as upmarket as Paddles but it consistently draws bigger crowds and plays pretty much exactly the same music (mind you, so does every other bar in Apia). It's definitely my favourite place to head to for a night out, as I'm guaranteed to either have company in the form of other volunteers who I go with, or work colleagues and other locals that I inevitably bump into whilst there. They also serve good cold beer.

One of the best things about Billy's is the sign above the entrance that outlines the conditions of entry that patrons must abide by. Most of the rules (see the picture) are ones we're used to seeing in Australia but I can't ever recall a bar or club explicitly denying anyone who is, or aims to be, "too cheeky".

Palusami

The Samoan dish most popular amongst all the volunteers is easily palusami. Along with taro, palusami is a staple dish, always prepared in an umu oven. The good news for us palagis however, is that you certainly don't need an umu oven to prepare your own.

To make palusami all you need are (relatively young) taro leaves and coconut cream. If you wish, you can add some onion and some varieties see small pieces of chicken or fish added too. Preparing your taro leaves is important. The thicker part of the stem running down the leaf needs to be trimmed back, and it's important to break off the tip of each leaf as you construct your palusami. Not doing so will make for a bitter taste (or so every single Samoan I've asked says).

Once you've prepared your taro leaves making the palusami is easy. Lay one big leaf flat in your hand and rip up another into three or four small pieces and place them on top of the leaf. Make a small pocket of the leaf and place some diced onion in and then pour coconut cream in. Fold the leaf over to enclose the pocket and then wrap the leaf with aluminium foil.

Place the palusami in a small baking tray and cook in a conventional oven for about 45-60 minutes at 200° C. Simply unwrap the foil and carefully lift the palusami onto your plate. Yum!

Pictured here is a photo from the night a few of us made our palusami. Along with the palusami we cooked a couple of red snapper caught that morning (simply salted and dusted with flour) and some taro, carrot and breadfruit tempura. Served with some cold Vailima (the local beer) it made for a perfect pseudo-Samoan dinner.

Monday, March 13, 2006

More Manono

Village life

Whilst staying on Manono I had the opportunity to learn a little about the nature of village politics and the role that matai play in the management of family and village affairs. Leota (pictured here) is a matai (chief) of his village and also the head of his aiga (extended family). He was more than happy to explain his responsibilities to both his family and his village and village politics more generally.

Leota was absent from his house for most of Saturday as he was busy attending his village's monthly fono ale nu'u (literally "meeting for the village"). Once a month the villagers meets to discuss (at length) any and all issues until a satisfactory outcome is reached. The nature of the discussion during these meetings is to avoid direct confrontation. Typically everyone will talk around an issue until a consensus or majority view is reached.

After the fono ale nu'u finished, Leota and all the other matai held another meeting to elect a new head matai for the village. The previous chief matai passed away in February and it was time to appoint someone in the position. Leota spoke only a little of the nature of the role but made it clear that the head matai effectively held the power of veto for any issue discussed during a fono ale nu'u. It would seem that this power is rarely used; any head matai who decides against the majority view too many times may well find themselves stripped of their position.

The head matai represents only one aspect of the village’s power structure, a largely intra-village focused one. The pulenu'u is a matai who has been selected to represent the village in all broader affairs, typically regional and national government driven. The best analogy we have in Australia is that of the town mayor. The head matai is normally not elected as the pulenu’u.

The fono ale nu’u exists to provide an arena for everyone to raise their concerns and discuss village business but specific village responsibilities fall upon a number of different committees. In this way the business of managing the village is shared amongst all of its inhabitants. The women’s committee, known as the aualuma, typically discuss beautification projects for the village and fundraising activities. Married and unmarried women over the age of 21 (or younger but out of school) attend these meetings. The aumaga or taulealea is the young men’s committee, where all untitled men over the age of 21 are typically responsible for managing the village’s plantations and other labour intensive tasks (fishing, grass cutting, etc., preparing umu). I’ve already mentioned the matai-only meetings that take place.

The hierarchy within villages would appear quite established. Leota certainly gave the impression that such is the case. However, as most of the village’s business is determined through consultation and communally reached decisions, there seems little opportunity for strongly individualistic behaviour. The pulenu’u or head matai for example, are going to find it difficult to exploit their positions for personal gain.

There would seem little to indicate that this manner of managing village business is going to change much in Samoa for a while. It is really only in Apia that there is a weakening of these structures. The main reason for this would be that many of people here only live in Apia because of work obligations. Even so, many return home to their own villages over the weekend, where their social and community responsibilities still lie.

Sunday, March 12, 2006

Manono

The Apolima Strait between the two large islands of Savaii and 'Upolu is home to the small islands of Manono and Apolima. Apolima is quite difficult to reach. Manono however, is much easier to reach and well worth visiting. It is, by choice of its residents, a very traditional island. Dogs are not allowed on the island nor are any vehicles (there aren't any roads anyway). It is the third largest island in Samoa yet only 3 sq km in size, with four villages and a population between 1000-2000.

There are two places open to visitors who wish to stay on Manono, one on the east coast, the other on the west. I just spent two nights staying at the latter, with Leota, his wife Sau and his several children (including young Aneti, pictured here "fishing" with his older brother Mose).

There's not a great deal one can do whilst on Manono except relax. Walking around the perimeter of the island takes somewhere between one and two hours. There are a couple of sites of interest, most notable of which (at least in theory) is the ancient star mound that is found on the top of Mt. Tulimanuiva. Sadly, the reward for making it to the top of the mountain is the sight of a mobile phone tower stretching some 50 metres into the sky. What remains of the 12-pointed star mound itself is obscured by vines and other foliage.

According to Leota, the family that owns the customary land on which the mountain lies made a deal with a telecommunications company to have a mobile phone tower installed. I got the impression that they did this without any broader consultation on Manono, nor indeed within their own village. It was only after the tower itself was installed that the rest of the island was able to bring a stop to things. Yet the tower remains.

The only upside of there being a huge tower on top of Manono is that climbing it affords you a spectacular 360° view. The other picture is the view from the tower back towards the side of the coast near where I stayed (the white specks are a couple of seabirds). Manono is completely surrounded by reefs so the water all around it is a magnificent cyan colour.